In the modern and civilized countries, people live lives in the network. When they wake up in the morning, they check their e-mail, make a quick phone call, walk outside (their movements are captured by a high definition video camera), get on the bus (swiping their RFID mass transit cards) or drive (using a transponder to zip through the tolls). They arrive at the airport, making sure to purchase a sandwich with a credit card before boarding the plane, and check their cell phones shortly before takeoff. Or they visit the doctor or the car mechanic, generating digital records of what their medical or automotive problems are.

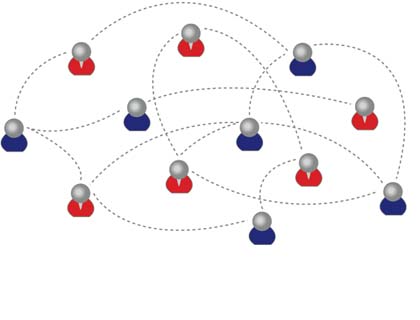

They post blog entries confiding to the world their thoughts and feelings, or maintain personal social network profiles revealing their friendships and their tastes. Each of these transactions leaves digital bread crumbs which, when pulled together, offer increasingly comprehensive pictures of both individuals and groups, with the potential of transforming their understanding of their lives, organizations, and societies in a fashion that was barely conceivable just a few years ago.

The capacity to collect and analyze massive amounts of data has unambiguously transformed such fields as biology and physics. The emergence of such a data-driven “computational social science” has been much slithery, largely spearheaded by a few intrepid computer scientists, physicists, and social scientists. If once they are to look at the leading disciplinary in economics, sociology, and political science, there would be minimal evidence of an emerging computational social science engaged in quantitative modeling of these new kinds of digital traces, computational social science is occurring, and on a large scale, in places like Google, Yahoo, and the National Security Agency. Computational social science could easily become the almost exclusive domain of private companies and government agencies. Alternatively, there might emerge a “Dead Sea Scrolls” model, with a privileged set of academic researchers sitting on private data from which they produce papers that cannot be critiqued or replicated. Neither scenario will serve the long-term public interest in the accumulation, verification, and dissemination of knowledge.

What potential value might a computational social science, based in an open academic environment, offer society, through an enhanced understanding of individuals and collectives? What are the obstacles that stand in the way of a computational social science? To date the vast majority of existing research on human interactions has relied on one-shot self-reported data on relationships. New technologies, such as video surveillance, e-mail, and ‘smart’ name badges offer a remarkable, second-by-second picture of interactions over extended periods of time, providing information about both the structure and content of relationships. Consider examples of data collection in this area and of the questions they might address. One of the most important questions to address to is internet.

The Internet offers an entirely different channel for understanding what people are saying, and how they are connecting. Consider, for example, in this political season, tracing the spread of arguments/rumors/positions in the Blogosphere as the behavior of individuals surfing the Internet .Where the concerns of an electorate become visible in the searches they conduct. Virtual worlds, by their nature capturing a complete record of individual behavior, offer ample opportunities for research, for example, experimentation that would be impossible or unacceptable. Similarly, social network sites offer an unprecedented opportunity to understand the impact of a person’s structural position on everything from their tastes to their moods to their health. In short, a computational social science is emerging that leverages the capacity to collect and analyze data with an unprecedented breadth and depth and scale.

Substantial barriers, however, might limit progress. Existing ways of conceiving human behavior they’re developed without access to terabytes of data describing their minute-by-minute interactions and locations of entire populations of individuals. For example, what does existing sociological network theory, built mostly on a foundation of one-time ‘snapshot’ data, typically with only dozens of people, tell us about massively longitudinal datasets of millions of people, including location, financial transactions, and communications? The panthers are clearly “something,” but, as with the blind men feeling parts of the elephant, limited perspectives provide only limited insights. These emerging data sets surely must offer some qualitatively new perspectives on collective human behavior.

There are significant barriers to the advancement of a computational social science both in approach and in infrastructure. In terms of approach, the subjects of inquiry in physics and biology present different challenges to observation and intervention. Quarks and cells neither mind when they discover their secrets nor protest if they alter their environments during the discovery process (although, as discussed below, biological research involving humans offers some similar concerns regarding privacy). In terms of infrastructure, the leap from social science to a computational social science is larger than from, say, biology to a computational biology, in large part due to the requirements of distributed monitoring, permission seeking, and encryption.

The networks available in the social sciences are significantly smaller, and even the physical (and administrative) distance between social science departments and engineering or computer science departments tends to be greater than for the other sciences. The availability of easy-to-use programs and techniques would greatly magnify the presence of a computational social science. Just as mass-market CAD software revolutionized the engineering world decades ago, common computational social science analysis tools and the sharing of data will lead to significant advances. The development of these tools can, in part; piggyback on those developed in biology, physics and other fields, but also requires substantial investments in applications customized to social science needs.

Unfortunately people living in the 3rd world countries are always the consumers consuming the products of other manufacturers from Europe, America and other industrial countries. Networks in the broad perspective are still a myth. In our country people are still unaware from the utilization of scientific inventions. We still consider ourselves the consumers not the inventors. It is very unfortunate to state that in our homeland Afghanistan the intellectuals and scholars are yet unarmed with the weapons of scientific technologies.