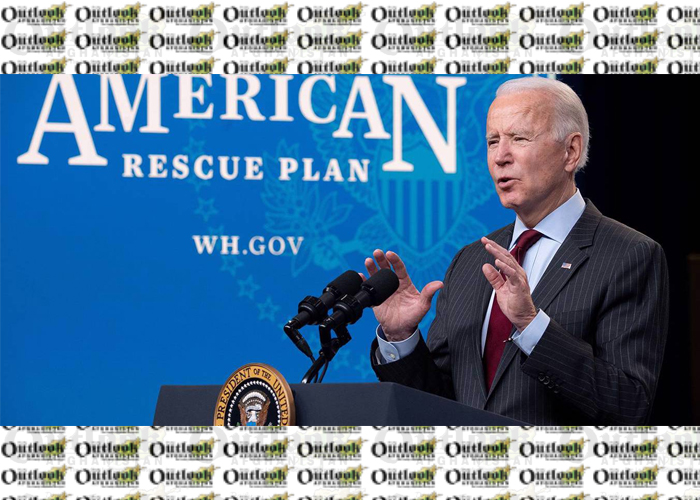

Slight increases in the rate of inflation in the United States and Europe have triggered financial-market anxieties. Has US President Joe Biden’s administration risked overheating the economy with its $1.9 trillion rescue package and plans for additional spending to invest in infrastructure, job creation, and bolstering American families?

Such concerns are premature, considering the deep uncertainty we still face. We have never before experienced a pandemic-induced downturn featuring a disproportionately steep service-sector recession, unprecedented increases in inequality, and soaring savings rates. No one even knows if or when COVID-19 will be contained in the advanced economies, let alone globally. While weighing the risks, we also must plan for all contingencies. In my view, the Biden administration has correctly determined that the risks of doing too little far outweigh the risks of doing too much.

Moreover, much of the current inflationary pressure stems from short-term supply-side bottlenecks, which are inevitable when restarting an economy that has been temporarily shut down. We don’t lack the global capacity to build cars or semiconductors; but when all new cars use semiconductors, and demand for cars is mired in uncertainty (as it was during the pandemic), production of semiconductors will be curtailed. More broadly, coordinating all production inputs across a complex integrated global economy is an enormously difficult task that we usually take for granted because things work so well, and because most adjustments are “on the margin.”

Now that the normal process has been interrupted, there will be hiccups, and these will translate into price increases for one product or the other. But there is no reason to believe that these movements will fuel inflation expectations and thus generate inflationary momentum, especially given the overall excess capacity around the world. It is worth remembering just how recently some of those who are now warning about inflation from excessive demand were talking about “secular stagnation” born of insufficient aggregate demand (even at a zero interest rate).

In a country with deep, longstanding inequalities that have been exposed and exacerbated by the pandemic, a tight labor market is just what the doctor ordered. When the demand for labor is strong, wages at the bottom rise and marginalized groups are brought into the labor market. Of course, the exact tightness of the current US labor market is a matter of some debate, given reports of labor shortages despite employment remaining markedly below its pre-crisis level.

Conservatives blame the situation on excessively generous unemployment insurance benefits. But econometric studies comparing labor supply across US states suggest that these kinds of labor-disincentive effects are limited. And in any case, the expanded unemployment benefits are set to end in the fall, even though the global economic effects of the virus will linger.

Rather than panicking about inflation, we should be worrying about what will happen to aggregate demand when the funds provided by fiscal relief packages dry up. Many of those at the bottom of the income and wealth distribution have accumulated large debts – including, in some cases, more than a year’s worth of rent arrears, owing to temporary protections against eviction.

Reduced spending by indebted households is unlikely to be offset by those at the top, most of whom have accumulated savings during the pandemic. Given that spending on consumer durables remained robust during the past 16 months, it seems likely that the well-off will treat their additional savings as they would any other windfall: as something to be invested or spent slowly over the course of many years. Unless there is new public spending, the economy could once again suffer from insufficient aggregate demand.

Moreover, even if inflationary pressures were to become truly worrisome, we have tools to dampen demand (and using them would actually strengthen the economy’s long-term prospects). For starters, there is the US Federal Reserve’s interest-rate policy. The past decade-plus of near-zero interest rates has not been economically healthy. The scarcity value of capital is not zero. Low interest rates distort capital markets by triggering a search for yield that leads to excessively low risk premia. Returning to more normal interest rates would be a good thing (though the rich, who have been the primary beneficiaries of this era of super-low interest rates, may beg to differ).

To be sure, some commentators look at the Fed’s balance-of-risk assessment and worry that it will not act when it needs to. But I think the Fed’s pronouncements have been spot on, and I trust that its position will change if and when the evidence does. The instinct to fight inflation is embedded in central bankers’ DNA. If they don’t see inflation as the key problem currently facing the economy, neither should you.

The second tool is tax hikes. Ensuring the economy’s long-run health requires much more public investment, which will have to be paid for. The US tax-to-GDP ratio is far too low, especially given America’s huge inequalities. There is an urgent need for more progressive taxation, not to mention more environmental taxes to deal with the climate crisis. That said, it is perfectly understandable that there would be hesitancy to enact new taxes while the economy remains in a precarious state.

We should recognize the current “inflation debate” for what it is: a red herring that is being raised by those who would stymie the Biden administration’s efforts to confront some of America’s most fundamental problems. Success will require more public spending. The US is fortunate finally to have economic leadership that won’t succumb to fearmongering.

Home » Opinion » The Inflation Red Herring

The Inflation Red Herring

| Joseph E. Stiglitz