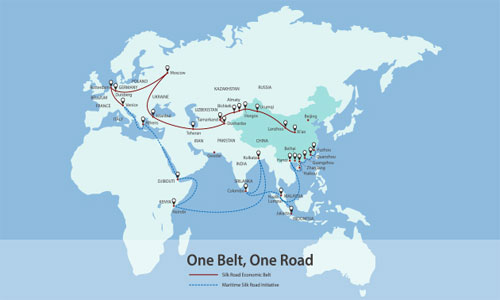

Seeking to revitalize the Ancient Silk Road, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in late 2013 on his visit to Central Asia and Southeast Asia. The initiative calls for constructing a unified domestic and international market through building infrastructure, extending trade and enhancing cultural exchanges. More than 100 countries and international organizations have joined this initiative and 86 countries, including Afghanistan, have signed the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with China so far.

It is self-evident that the megaproject of BRI carries much significance for Afghanistan, which intends to regain its historical position as an “Asian transit and trade roundabout” connecting South Asia to Central Asia and East Asia to West Asia. That is, Afghanistan is situated at the heart of Asia and its provinces of Bamyan, Balkh, Kabul, Herat and Kandahar formed some of the key Silk Road passages through which business, culture, religions and syncretic philosophies flowed to Eurasia. To promote transnational projects, Kabul government initiated the Regional Economic Cooperation Conference on Afghanistan (RECCA) in 2005 the seventh meeting of which entitled “Deepening Connectivity and Expanding Trade through Investment in Infrastructure and Improving Synergy” was held in Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, last year. Since October 2016, Afghan officials showed interest in joining the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project – in which more than $60 billion has been invested so far – that can support Afghanistan to reinforce its trade across the region. Afghanistan also became a permanent member of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2017. According to Afghan Deputy Foreign Minister Hekmat Khalil Karzai, “Economic development process along the Silk Road will reshape the international development order that has been centered in our region and carried great significance for human development in the 21st century”.

In the 12th Silk Road Mayors Forum, hosted by Kabul last year, Afghan President Muhammad Ashraf Ghani said that Afghan nation and state were determined to regain their country’s former status as the “center of the Asian crossroads” despite the ongoing challenges and urged provincial mayors to network with their Silk Road counterparts. Mayors, diplomats, scholars and business leaders from the Silk Road countries discussed the civilization of the Silk Road era, regional cooperation and partnership and their shared interests in the forum. Hence, Afghan officials show keen interest in the BRI.

Speaking in the opening ceremony of 5th China-South Asia Expo in Kunming on June 14, Afghan second deputy Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Haji Muhammad Mohaqiq said that China is the largest foreign investor in Afghanistan and praised China for its effective role in trade and investment in the country since 2001.

The year 2016 was very productive for China and Afghanistan for three main reasons: First, MoU on the BRI was signed between Kabul and Beijing; second, the first Chinese cargo train carrying goods valued at $20 million arrived in the northern Afghan port city of Hairatan after about two weeks of journey via Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. This 84-car train which traveled 3,000-kilometer rail line departed from Chinese port city of Haimen near Shanghai. Planning for a transit schedule of two trains per month, China will export textiles, electronic products and construction material to Afghanistan. Third, Kabul-Urumqi direct flight was resumed – after being closed at the end of 2012 – and there is a flight every once in a week from Kabul to Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, and vice versa cutting travel time between the two cities from 13 hours to 3 hours.

Within the past several years, China-Afghan officials floated the idea of opening up Wakhan Corridor, a barren panhandle of Badakhshan province in the far northeast of Afghanistan bordering Chin’s Xinjiang region. This mountainous 2000-year-old caravan route – sandwiched between China, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Pakistan and acted as a buffer between the Russian Empire and British Empire in 19th century – is about 350 km long and 13-65 km wide. Nazif Shahrani points out in “The Kirgiz and Wakhi of Afghanistan: Adaptation of Closed Frontiers and War” that Wakhan Corridor was one of the key routes for merchants and traders between India, China and cities like Bactria and Bukhara in modern-day Afghanistan and Central Asia until the downfall of Mughal Empire in India. Despite the past political upheaval, Wakhan remained unscathed and a large portion of Wakhan residents are unaware of the Taliban’s regime (1996 – 2001) and US invasion in Afghanistan. Notwithstanding this fact, Sino-Afghan trade passes through a third country and the initiative to open a direct border between Afghanistan and China yet to emerge. Opening Wakhan Corridor through building highway for direct bilateral trade between the two countries will be mutually beneficial for both sides.

There are some railway track projects, which will contribute to regional connectivity, topping the priority list of Kabul government: Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline, the power project for Central Asia-South Asia (CASA-1000), and 500 KW power transmission line of Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan-Tajikistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan (TUTAP).

Afghanistan has huge potential energy. It is estimated to have the potential for producing 223,000 MW of solar energy, 23,000 MW hydropower energy and 68,000 MW of wind energy.

To be continued…

Home » Opinion » Afghanistan’s Role in the Belt and Road Initiative (Part 1)

Afghanistan’s Role in the Belt and Road Initiative (Part 1)

| Hujjatullah Zia